An alternative take on grading fancy-coloured diamonds

by charlene_voisin | May 1, 2013 9:00 am

By Branko Deljanin

[1]

[1]

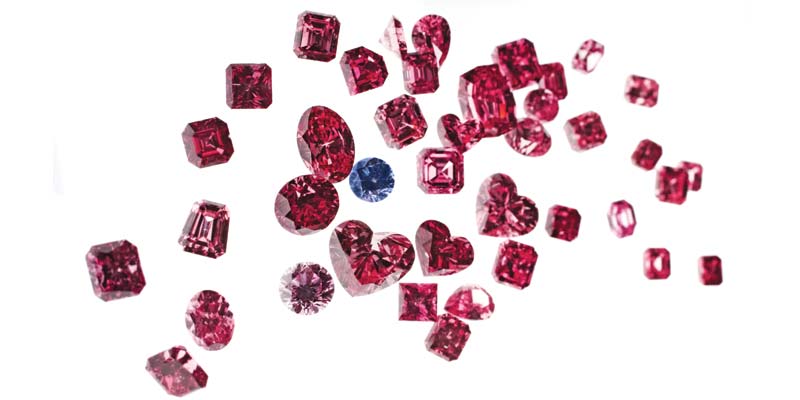

One in 10,000 natural diamonds has enough colour to be deemed a fancy-coloured stone. Browns are the most common, and some mines like Rio Tinto’s Argyle in Australia produce large quantities of these diamonds, which are marketed as ‘champagne’ in the lighter yellowish brown range and ‘cognac’ for the darker orangey brown variety. Confirmation the Argyle mine will go out of production in 2018 has fuelled increased interest among private buyers and investors, both in Canada and abroad. In addition to large-size, high-clarity champagnes and cognacs, rarer grey, yellow, orange, olive, green, blue, and pink natural diamonds have also gained more notice. With supply decreasing and demand increasing, there is a natural correlation driving prices to adjust as well. Let’s take a closer look at fancy-coloured stones and how their rarity affects value.

Background

[2]

[2]Coloured diamonds were not talked about much in the 1960s; auction houses only listed a diamond as ‘fancy,’ ‘canary,’ or ‘cinnamon,’ with a black and white photograph shown in catalogues and very little other information included. In the late 1980s, the perception surrounding fancy-coloured diamonds began to change when the .95-carat ‘Hancock Red’ sold for almost”¨ $1 million US per carat. This also seems to be the time when prices began to rise, as demand for rare colours increased and media became more interested in these unknown beauties. At the same time, the Argyle mine began producing steady amounts of pink diamonds in all sizes, along with the more common brown diamond. The new mine supplied enough volume to make pavé-setting pink diamonds feasible.

By the 1990s, designer Ralph Esmerian had introduced pink diamonds to the U.S. market. It was around this time the 5.11-carat ‘Moussaieff Red Diamond’ was found in a river in Brazil and later sold to a collector for $2 million US per carat. Imagine it—$10 million US for one gram of carbon that nature created over millions of years through high pressure and temperature into the rarest colour of all, the fancy red diamond.

The advent of the Internet has allowed a wider audience to come to know fancy-coloured diamonds; dealers with access to large and important stones actually have a waiting list of clients keen for specific colours and sizes. The celebrity factor also helps.

Long prized for their rarity and beauty, coloured diamonds are hot-ticket items today, thanks in part to actresses such as Jessica Biel, who received a pink diamond engagement ring from Justin Timberlake. And who could forget the 6.10-carat pink sparkler Jennifer Lopez received from Ben Affleck.

Aside from adornment, however, there’s another reason for their popularity: investment. While fancy-coloured diamonds appear attractive among investors, great caution is required when purchasing them for this purpose. As with all investments, buying low, or in this case, farther up the supply chain, is key to realizing a return. Also, rarity is a significant factor in making a worthwhile investment.

Describing and appreciating colour

[3]

[3]After brown diamonds, yellows are the most common of the fancies, but still rarer than colourless diamonds of the same clarity. Larger quantities of light yellow diamonds were found in the late 1800s in South Africa’s Cape province. Since then, the term ‘cape’ has been used to describe yellows that have ‘cape serious’ spectra (415, 452, 478 nm peaks) regardless of origin. The rarest yellow diamonds are highly saturated and show pure yellow hues. In the 1950s, the industry referred to these colours as ‘canary,’ but in today’s market, they are most commonly referred to as ‘intense’ and ‘vivid’ yellow. Some strong (i.e. intense and vivid) canaries may also have an orange modifier. Greenish yellow diamonds of natural colour are also rare, along with deep yellow diamonds with brownish, greyish, orangey, or olivish modifiers, which are also coveted by collectors and investors. Compared to other fancy colours, yellow diamonds are more abundant in nature, although their value jumps significantly when the colour is stronger than the ‘Z’ master stone.

Grading colour of fancy diamonds is perhaps the most difficult of the four Cs to determine. GIA uses six categories to describe their grades: ‘fancy light,’ ‘fancy,’ ‘fancy intense,’ ‘fancy dark,’ ‘fancy deep,’ and ‘fancy vivid yellow.’

Although this system is most widely used, grading colour remains a subjective exercise and open to further discussion. For instance, another system exists to describe the different shades of yellow diamonds, using terms such as, ‘canary,’ ‘chartreuse,’ ‘golden,’ ‘lemon,’ and ‘straw.’ These common colour names and many others are defined in the glossary section of Stephen Hofer’s book, Collecting and Classifying Coloured Diamonds.

According to Hofer, the problem with colour grading is the common belief that it should be straightforward, black and white so to speak. After all, how hard can it be to determine what colour something is?

“In fact, the colour grade is only a quick and simple way to denote the hue, lightness, and saturation of a coloured diamond by lumping them into a limited range of 27 colours (hues and modifiers), and a limited range of six colour grades,” he says. “The problem begins with the diamond industry’s reliance on subjective colour grading procedures, which can only result in confusion and errors in describing colour to others.”

If the diamond industry gently moved in the direction of using instrumental methods like spectrometers to measure colour in diamonds, and then use this numerical colour data as a valid starting point to begin a more accurate and precise method to assign colour, we would not only create a better understanding of colour, but introduce wholesalers and retailers to a greater range of colour in diamonds.

Colour in diamonds is 3-D, defined by saturation”¨ (i.e. X on the scale, indicating ‘fancy’), tone (i.e. Y, which represents how light or dark it is), and hue (i.e. Z, meaning general colour [e.g. yellow]). Hence, the colour grade ‘fancy light yellow,’ for example. Having exact XYZ co-ordinates can help determine grade objectively, and therefore, assign it more accurately.

If diamond cutters incorporated this 3-D concept, they would likely develop new ways of cutting diamonds yielding more varieties of colour that may appeal to consumers looking for a wider range of options.

Testing and grading coloured diamonds

[4]

[4]Coloured diamonds are unique and more challenging to grade than their colourless counterparts, as no two are alike. Each stone may have secondary hues besides the primary colour at varying intensities. They are graded by comparing to a master set of the same hue, or with non-transparent Munsell chips of similar hue, tone, and saturation. Few labs have a comprehensive suite of some colours. Even so, colour grading is inherently subjective without the use of spectrometers, which, as mentioned earlier, can measure colour more precisely. This method, however, has traditionally not been used by most labs, as it is more time-consuming, both in application and interpretation of the results. At our lab, gemmologists employ this method and indicate spectra results on diamond reports. While 3-D colour grading is possible, educating gemmologists, traders, and eventually consumers is necessary to understand how these numbers translate into a fancy colour grade system, such as GIA’s or Hofer’s.

Since values are based on grades, a report from a reputable gem laboratory should accompany any important coloured diamond weighing more than .50 carats to verify it as natural. The issue of testing and grading is three-fold:

Identification and colour origin

Testing with standard and advanced instruments is critical to properly identify and assign colour origin (i.e. natural, treated, or synthetic). I had the opportunity to study and certify part of a collection of ‘chameleon’ fancies. When heated to approximately 120 C, they exhibited temporary colour changes from olive to orangey yellow and some continued to do so after prolonged storage in the dark. This phenomenon is rare and increased the stones’ value by 10 to 20 per cent compared to one of the same quality that does not change colour.

Accuracy

In his book Collecting and Classifying Coloured Diamonds, Hofer uses nature-based terms such as ‘lemon,’ ‘honey,’ ‘canary,’ ‘rose,’ and ‘olive’ among others to describe colour. Perhaps the best methodology is to combine a ‘dry’ colour grade, such as ‘Fancy deep grayish greenish yellow’—which is GIA’s widely accepted grade terminology for coloured diamonds—with an additional comment like ‘Known in the trade as olive colour’ and scientifically position this colour in a 3-D system (i.e. numerical value).

Repeatability

Repeatability refers to the ability of a single laboratory to examine a coloured diamond and then at some later date, re-examine the same stone and reach the same conclusion. Similarly, it is important the colour grade assigned by one lab can be verified when the stone is submitted to a second one for testing. This is known as ‘reproducibility.’ Currently, there is very little repeatability and reproducibility in coloured diamond grading. In short, the entire colour grading system is in need of an overhaul so that each colour grade is assigned more accurately using modern technology, and less subjectively (i.e. relying solely on master sets and the human eye).

Fancy shapes for fancy colours

[5]

[5]Shape refers to the ‘canvas’ the diamond cutter chooses to display his artwork. Generally, a cutter selects a shape that yields the most weight, although cutters sometimes sacrifice a little weight in favour of better clarity or a shape outline that will be most flattering when seen in the face-up position. In general, rounds promote brilliance, hence the colour is slightly lower in saturation and slightly lighter in tone. Round brilliants are the most expensive, with premiums in excess of 40 per cent, especially in the rarer larger sizes. Shapes such as marquise, pear, and oval cause light to travel a longer distance within the stone, resulting in stronger colour in the face-up position. This is especially true with radiant-cut stones, as many cutters use this shape to ‘squeeze’ more colour out of the diamond in the face-up position. However, some radiant-cut stones do not look ‘pretty’ and in some cases, appear dull, since light is not reflecting toward the viewer’s eye. Dealers don’t often acknowledge this. In my opinion, cutters should be more interested in creating the most beautiful stone, and not simply trying to get a certain colour grade on a lab report.

Pricing fancy-coloured diamonds

In 2011, an Israel-based gemmologist launched an online wholesale pricing system for fancy-coloured diamonds that is based on the use of a digital colour master set. While the intent is noteworthy, some gemmologists, myself included, see the issue of colour grading as more complex. Although this system may better communicate and standardize colour grading, as well as provide a price range for a specific colour, some would argue it doesn’t take into account a diamond as a 3-D object with varying colour intensity on different facets. As such, pricing accuracy may be called into question.

Prices are dependent on the level of the market. Once a stone is polished, a wholesale dealer sells the stone based on the colour grade it receives from a laboratory. As stated previously, there are serious problems with the accuracy of the current colour grading system. If the industry takes steps to standardize coloured-diamond grading, the market will help dictate a stone’s value in a more consistent manner.

For now, value can be determined through various channels. For smaller commercial diamonds like yellows and browns, labs generally compare stones of similar characteristics. In the case of rarer colours, such as pink or green, as well as larger yellow stones, it is not unusual to consult active dealers. Labs may also check prices with major retailers for diamonds of similar cut, carat, clarity, and colour.

Market situation for coloured diamonds

[6]

[6]At present, the market is strong for high-quality coloured diamonds, given their shortage.

Tsafrir Romi of Brilliant C in Toronto sees natural yellow and pink diamonds as trending strongly, which correlates to higher prices. “The demand has increased globally, but especially in the Far East and Australia,” he explains. “For example, in the past six months, the wholesale price for one-carat diamonds in natural fancy yellow has increased from $3000 US per carat to $4500 per carat, while natural fancy yellow diamonds in the one-carat to three-carat VS clarity range can vary from $6000 US per carat to $70,000 US.”

Should private individuals collect/invest in natural coloured diamonds? Supply seems to be declining, and fewer and fewer rare fancy diamonds are coming out of existing mines. And while there are plenty of websites and other sources of information extolling the enormous investment potential of coloured diamonds, there is reason for caution. A consumer who buys a not-so-rare .50-carat fancy yellow diamond may not realize the return on investment they’re hoping for in selling it a few years later beyond perhaps the rate of inflation. A five-carat vivid yellow diamond, however, is a different story.

Additionally, the point in the chain at which the diamond is purchased also plays a factor. If an investor buys a fancy-coloured diamond at retail, he or she will have a longer wait for the stone’s value to increase, as opposed to purchasing it farther up the supply chain. As a long-term investment (i.e. ideally 10 years) or as a hedge against inflation, higher-quality, fancy-coloured diamonds in larger sizes and with exceptionally rare or highly saturated colours will likely show the fastest and highest gains in price and value, although predicting a time frame is difficult to calculate. Some experts even say it can take decades for an individual to realize on their investment to any significant degree. Like any other speculative venture, numerous factors are at play when investing in diamonds, making what some describe as a ‘sure thing’ not entirely the case. Â

Consumers are only just beginning to understand what rarity means in a coloured diamond, and as word spreads, their value should increase. For example, most know pinks and blues are rare, but few are even aware fancies like violet, milky white, purple, olive, and orange exist. With less and less fine material coming out of the ground, a greater percentage of unusual and rare colours will become more interesting as investments.

[7]Branko Deljanin, B.Sc., GG, FGA, DUG is head gemmologist and president of Canadian Gemological Laboratory (CGL) in Vancouver. He is a regular contributor to trade and gemmological magazines and has presented reports at a number of research conferences. Deljanin is an instructor of standard and advanced gemmology programs on diamonds and coloured stones in Canada and internationally. He can be reached at info@cglworld.ca[8].

[7]Branko Deljanin, B.Sc., GG, FGA, DUG is head gemmologist and president of Canadian Gemological Laboratory (CGL) in Vancouver. He is a regular contributor to trade and gemmological magazines and has presented reports at a number of research conferences. Deljanin is an instructor of standard and advanced gemmology programs on diamonds and coloured stones in Canada and internationally. He can be reached at info@cglworld.ca[8].

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Fig-6-different-shapes-for-Argyle-pink-and-blue-diamonds.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Fig-2-Brown-and-pink-diamond-crystals-form-Argyle-mine.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Fig-4-Testing-of-Fancy-intense-pink-Argyle-diamond-at-gem-lab.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Fig-5-Chameleons-Nice-Diamond.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Fig-8-5.01ct-Fancy-dark-orangy-brown-diamond-also-called-CHOCOLATE.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Fig-3-O.87-ct-Fancy-light-yellow-round-CAPE.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Branko.jpg

- info@cglworld.ca: mailto:info@cglworld.ca

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/an-alternative-take-on-grading-fancy-coloured-diamonds/